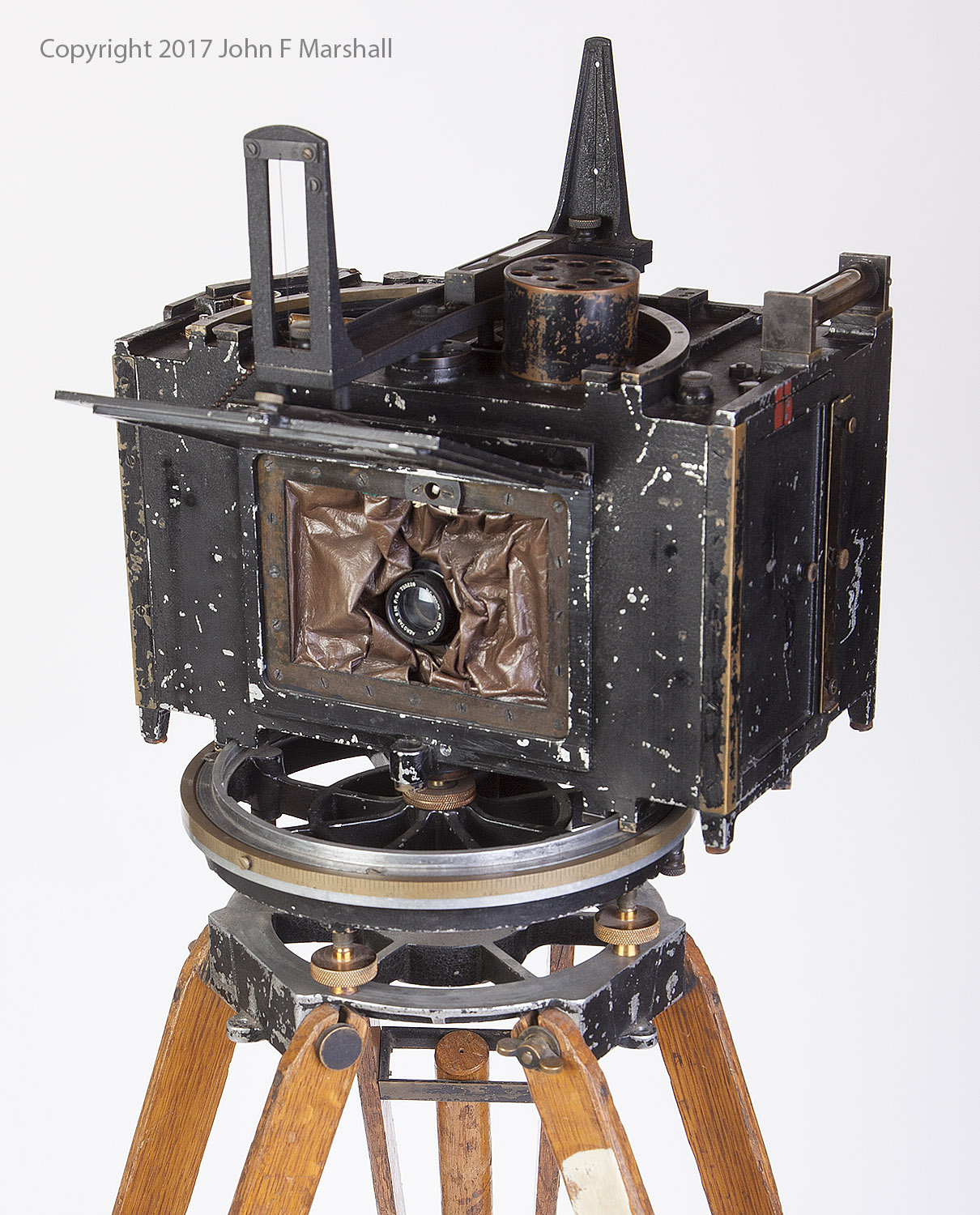

Osborne Panoramic Camera

Photo Recording Transit, circa 1930

In the 1930s, the U.S. Forest Service embarked on an ambitious photography project in Oregon and Washington. As part of their fire detection program, they took panoramic photographs from every lookout site, of which there were 813, including state lands and National Parks. At each site, three photographs were made, each taking in a 120- degree angle of view. At the height of the project in 1934, six photographers- mostly forestry students from the University of Washington, or Oregon State College were employed. Four or five panoramic cameras were in use. The objective of the project was to determine whether there was adequate visual coverage of all forest areas for fire detection purposes. Contact prints were made from the negatives, and used to analyze the seen area, by making comparisons between photo sets from adjacent lookouts. Later on, prints with notations of geographic features were kept at each lookout station. When the man or woman occupying a lookout station saw a "smoke", they could give a precise bearing, and describe the location according to landmarks. A complete set of prints was also kept at the regional office in Portland, all of which can now be found at the National Archives and Records Administration in Seattle, Washington. They are known as the "Osborne Panoramas", in recognition of William B. Osborne, who designed the panoramic cameras. I have been privileged to look at many of these historic images

Kodak Peak SE Glacier Peak Wilderness Area in the Washington Cascades. George B. Clisby 1934, from the National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle WA. The numbers at the top of the photo, refer to compass bearings or azimuth. South is 180 degrees. East is 90 degrees.

William B. Osborne, was the same ingenious man who designed the Osborne Fire-finder, a rotating metal disk with a special sight, that is a fixture at fire lookouts even today. In technical terms, the panoramic camera is referred to on it's name plate as a "Photo Recording Transit. The "transit" label comes from the fact that this piece of equipment has many of the features of a survey instrument, that allows it to be oriented in a very precise way. In order to attain 120 degrees of view, the Photo Recording Transit had a lens that rotated during the exposure. Curved rails inside the film chamber, kept distance from lens to film a constant. A wind-up clock motor caused the rotation. The earliest prints I have found are dated 1929, and do not take in as much angle as the later ones, indicating there was some advancement in design. Leupold & Volpel a Portland, Oregon company that made survey instruments at the time, built the Photo Recording Transit, using a six inch (175mm focal length) lens made by C.P. Goerz. Leupold & Volpel was already making the Osborne Fire-finder, so it was a natural that they were asked to manufacture the cameras. Thousands of the Osborne Fire-finders were made, whereas ten or fewer of the Photo Recording Transits were ever made. Leupold & Volpel later became Leupold & Stevens, and now does business under the name Leupold with a focus on rifle scopes, spotting scopes, and binoculars.

Photo Recording Transit No. 6, photographed at the Fire Lookout Museum in Spokane, WA

Having looked at hundreds of Osborne Panoramas, and replicated many, my curiosity to see one of the actual panoramic cameras (recording transits) became insatiable. Ray Kresek who lives in Spokane has been the keeper of history with regards lookouts, and has at his home a small museum called the Fire Lookout Museum, which runs as a non-profit organization. In 1995, Photo Recording Transit No. 6, was acquired from legendary U.S. Geological Survey scientist and photographer Austin Post. Post had taken possession of the camera in 1972 from the Forest Service, which declared it obsolete. I made the journey from Wenatchee to Spokane with a car-load of studio equipment- lights and backdrops. Kresek generously let me set up for the whole afternoon in his basement. I must say, I about fell over when I saw this piece of history. The sheer size, beauty, and complexity of the Photo Recording Transit is mind boggling. There are multiple brass adjustments to make sure the equipment is in precise orientation but no aperture settings. Exposure is determined by the speed at which the lens rotates, which is controlled by "flutter fans" providing speeds from 1/5 second to 2 seconds.

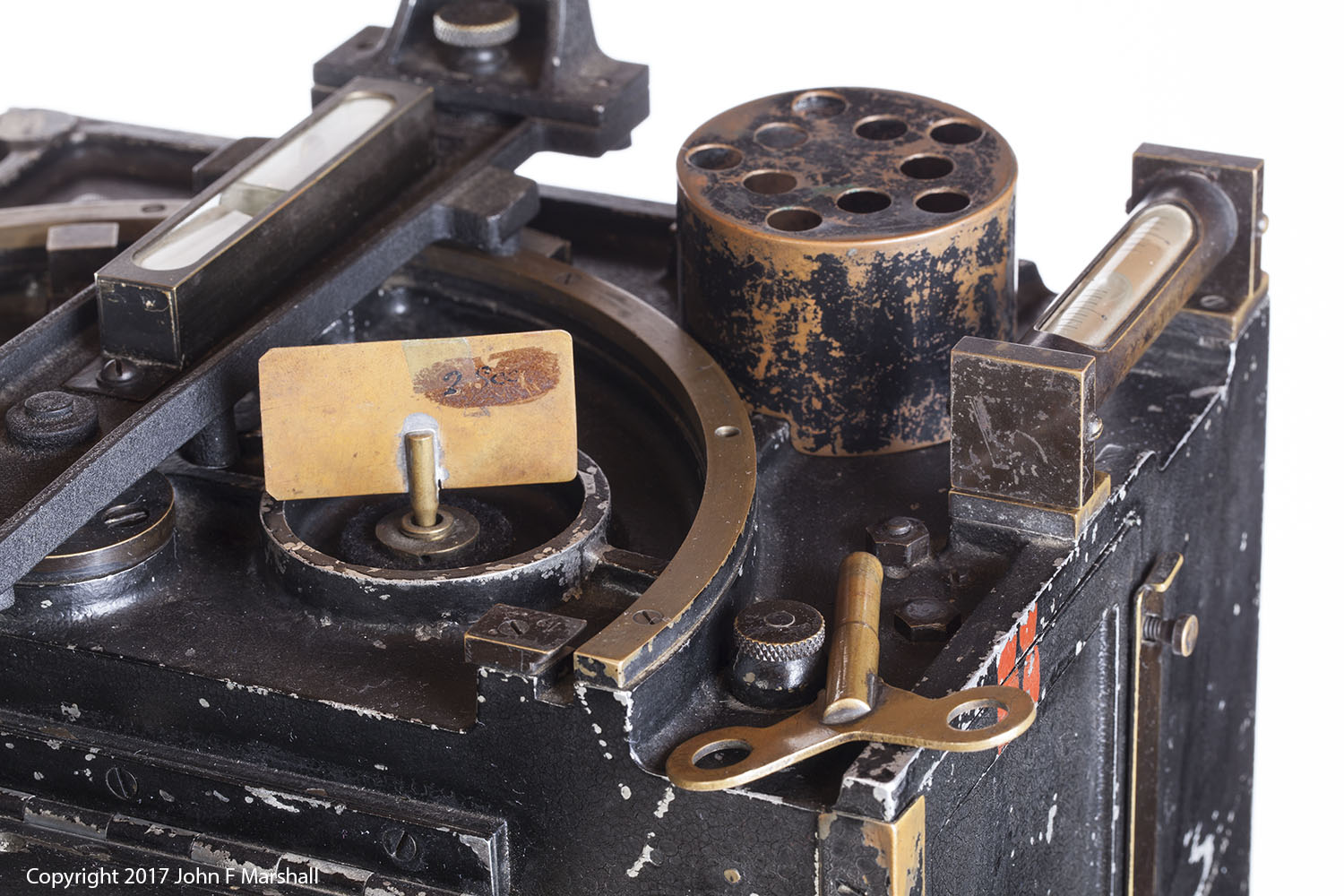

The 5.9 inch focal length C.P. Goerz lens was a standard item of the time. This particular one has serial no. 75,526. Goerz was a German company with an American branch in New York. The key at upper right was used to wind the clock motor.

Top view showing brass fan which was the only exposure control. Various size fans were used to slow the lens rotation. The perforated cap was placed over the fan to reduce the effect of any wind.

The Photo Recording Transit along with tripod head, and legs weighs 75 pounds. In his 1985 memoir We Climbed the Highest Mountains, Albert Arnst who headed the project gives some details as to how the work was accomplished. There were roads to some of the lookout stations, but others could only be reached by trail. If the distance was four miles or less, the young men packed the equipment in on their backs. If the distance was further, they had use of a pack horse. On extended trips to multiple back-country sites, they hired outfitters with pack strings. In all 3,000 miles was traveled with horses to reach all of the lookout stations. The long term average was two to three days per station photographed. Photographs were taken around 9:00 in the morning, noon, and 3:00 in the afternoon. Six-inch-wide film from Kodak (typically infrared) came in rolls that held four to six shots. Photography was usually done on the catwalk outside of the lookout cabin, but in some cases off the roof! At some locations, there was no existing lookout structure, just a site where one was being considered. At these undeveloped sites, photographers needed a precise way of determining direction. Polaris- the North Star, provided the direction of true north. At night, an attached device called a solar-scope was aimed at Polaris to orient the Photo Recording Transit for the next day's shooting.

Today, we owe a debt of gratitude to the U.S. Forest Service, William B. Osborne, Leupold & Volpel, Albert Arnst, and all of the sturdy young men, who labored up mountain trails. The effort was aimed at fire control, but inadvertently left a great scientific and historic legacy.

Forest Service Truck at Foreman's Point, southeast of Mt. Hood in 1934. The large box at left held the Photo Recording Transit.