Fire in Tumwater Canyon

July 27, 1994 was more than my forty-third birthday. It was my first opportunity to view a full fledged forest fire. Hatchery Creek Fire west of Leavenworth, Washington had ignited three days earlier from lightning. I had taken a fire ecology class as a graduate student at the University of Idaho, and had participated in some prescribed burns, but this was different. My Federal Express delivery driver had just driven through Tumwater Canyon and suggested I have a look. "You mean you can see flames?".......... "Yeah you can." That's all I needed to hear. I arrived just in time to take a picture of a group of tourists, with an "oh my god" expression on their faces. It's hard to know what is on someone's mind, but they were probably thinking "isn't this awful." For me it was "isn't this amazing, and yes a bit scary." Within a few minutes a sheriff's deputy showed up to kick us all out.

Reluctant to leave an extraordinary photo opportunity, I drove a mile down the road to Swiftwater Picnic Area where two rather experienced looking firefighters stood by an interpretive sign assessing the fire. A state trooper showed up to enforce the closure. I begged to stay, playing the National Geographic card. It was true, I was a published National Geographic photographer, from Mt. St. Helens. To my relief the trooper said "yes, if it's okay with those guys"......... and it was. I felt like I was watching one of nature's greatest spectacles, like a great storm at sea. So began a project of documenting how landscapes change following big fires, that has continued for more than twenty years. Oh, and the photograph below at left did make it into a National Geographic book- Raging Forces.

July 27, 1994, across the Wenatchee River from the Swiftwater Picnic site, the fire is burning in a dense patch of young Douglas-fir trees. At right is seen the aftermath a couple of months later.

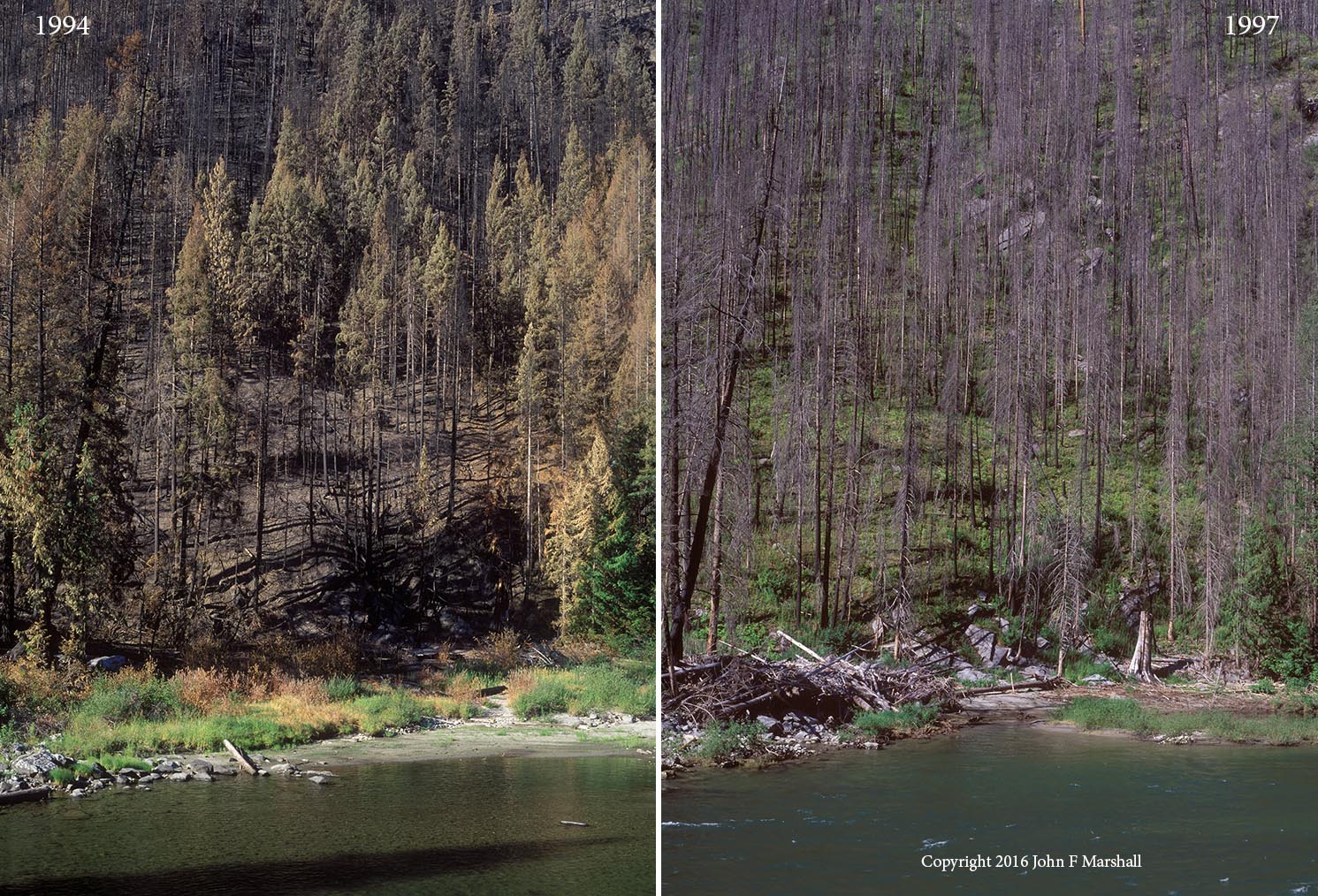

In three years time, the needles have fallen off of the fire-killed trees, but nearly all are still standing as snags. The ground is well covered in grasses, herbaceous vegetation and emerging shrubs.

After sixteen years, most of the snags have fallen. Conifer trees including lodgepole pine, Douglas-fir, and grand fir have established themselves. Red stem ceanothus is in abundance.

At year twenty, the Chiwaukum fire ignited outside of Tumwater Canyon, and burned part way into it. Firefighter/EMT Michael Stanford with Lake Wenatchee Fire and Rescue took this amazing photo.

When the Chiwaukum Fire reached the Swiftwater site, the combination of resin-rich green trees, snags, and logs was a recipe for very hot burning. Much of twenty years re-growth was wiped out. Most of the stored carbon was released to the atmosphere.

More was lost than the young trees. Most of the snags and logs created by the 1994 fire were wiped out in the fire of 2014. Snags are used by birds. Logs are important for retaining moisture in soil and as wildlife habitat.

2016- Two years have passed since the Chiwaukum Fire, twenty-two years have passed since the Hatchery Creek Fire. Grasses, shrubs, and herbaceous plants are growing back. A small patch of surviving lodgepole pine trees as seen at upper left, will re-seed the hillside.

The hillside across from Swiftwater Picnic Area is a bit extreme. Other places in Tumwater Canyon did not burn so hot. In actuality, Chiwaukum Fire of 2014 did not burn much farther than Swiftwater. As often happens, when fire reaches an area burned in the recent past, Chiwaukum fire lost its momentum. Much of Tumwater Canyon continues to have the spectacular fall color from shrubs that established after the fire of 1994. The Swiftwater site is instructive of what can happen. When a forest gets too dense, it is prone to high severity fire, leaving behind a dense patch of snags and logs. When it burns a second time, the fire can be intense. If there was such a thing as a time machine, I would go back to 1900, and take a photo. The forest would have been much more open due to frequent low intensity fires. We interrupted the natural fire cycles with fire suppression. When the dam of fire suppression finally broke, it let loose a flood of fire. As for the future, my guess is that the hillside across from Swiftwater Picnic site will be populated with lodgepole pine, and will not burn again for many years, as there will be too little fuel on the rocky slopes to carry a fire.

A topic that comes up after every fire is whether to salvage log or not. In this case it is hard to imagine how salvage logging could be done safely and efficiently in a narrow canyon along a highway. Even if it could, most of the trees were too small to be of much value. The trees with the greatest economic value were the few large ones, which also had the greatest value to wildlife.

The intense fall color seen here is the result of the 1994 Hatchery Creek Fire. Colorful shrubs took the place of the pine and fir trees that died in the fire. Fortunately some of the conifer trees lived to provide a nice dark green contrast, and diverse habitats for plants and animals.

This worn-out sign at Swiftwater Picnic Area has been in place since before 1994. I find it emblematic of how we are treating our National Forests. The sign should read Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest, as the two forests were combined because of budget cuts. One would think that on a popular tourist route like Highway 2, we would have a nice up to date sign, and maybe one that told the fire story, as well as the Indian legend.

The sequence of pictures shown with this article have been supported over the years by the U.S. Forest Service including the Wenatchee River Ranger District, the Fire Management Office of the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest, and the Wenatchee Forestry Sciences Lab.